Built for Industry: Daniel Eatock

For the latest instalment in our Built for Industry interview series, we caught up with artist, designer and Ravensbourne alumnus Daniel Eatock at his studio in Hackney.

Since graduating from Ravensbourne, Daniel has had work commissioned by a variety of clients across the globe, notably to design Channel 4’s Big Brother visual identity. Having left Ravensbourne in 1993, he now returns in a different capacity: facilitating and curating a project with current students to reimagine and reframe his work.

We spoke to Daniel about his life, work, philosophy and experiences of Ravensbourne both new and old.

Tell me about yourself, your academic journey and your early life experiences that led you to Ravensbourne.

My dad was a designer and my mum was a typographer. All through my childhood, I was encouraged to be creative, so I was doing drawings and I was always the one at school that would do the posters if there was a car boot sale or a village fete, I would always be the kid that was asked to do that.

After secondary school, I did a BTEC in Graphic Design at Wigan College. When it came to my degree, I looked around at a lot of different universities. I grew up in Lancashire and I wanted to come to London.

Daniel quote

I applied [to Ravensbourne] and I got on the course. I remember really clearly at the interview that the questions we were quite provocative, in a good way. It just felt dead right. The course was organised, disciplined and just felt figured out. I immersed myself in there. I really loved what I was doing. ”

The first year was a lot to do with practical design lessons, but in the second year, I started to explore a more conceptual, ideas-based practice. I started to discover my own voice as a young designer. Then I went to the Royal College of Art (RCA), but Ravensbourne was a perfect building block for that trajectory. It was a good mixture of practical and academic.

Once you’d graduated from your MA programme, how did you navigate getting into the industry?

It all happened organically. When I was at college, I just trusted that if I prioritize the work and made sure that each thing was the best it could be, then that would lead to opportunities.

As I was getting close to finishing at the RCA, I had a tutor that had recently travelled to the States and visited a contemporary art museum. It had internships and designers could work within an internal design department and he felt that my work would be really great if it was put into a real context of an art museum. I contacted the museum, went over for an interview and then I got the place. It felt like a continuation of education. I did a two-year BTEC, three-year degree at Ravensbourne, two-year MA, and then a one-year internship at the Walker Art Center, and they all feel almost like they were designed to go together like a jigsaw puzzle; each one was a bit more intense, but they slot together brilliantly.

You're now established in the design industry and you've got a really clear identity in your own practice. Which of your projects that over the years has presented the biggest challenge and which was the most gratifying?

The reason for having [my own studio] was to take on board bigger projects that I wouldn't be able to get as an individual, but the work my studio was taking was to buy me time so I could focus on work which wasn't commissioned. I was lucky that I've had clients that were understanding of that. I've had Channel 4, I’ve had Canal+, I had the Serpentine Gallery. I've had people that were accepting that the thing I was making was only half of what I do, but they knew that I was also practicing as an artist, so that's always been the challenge and still remains so.

The most satisfying thing is just keeping everything afloat, because you never have one thing on the go at the time. There's always a mixture of things; a book, an exhibition, a commission. To do well, I need to be in a good place, so I need to be reading, I need to be a good parent to my daughter, I like to run and climb, I like to eat healthy. When all those things feel balanced, that's when I feel at my best. It's just about trying to keep everything good and acknowledging when it’s good because it is good most of the time, but don’t get too hung up on the problems. Just accept them and move forward.

And the most formative to your style?

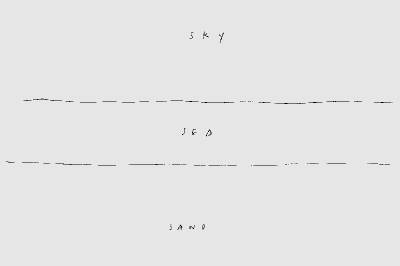

I don't use the word ‘style’ because style suggests aiming to create something that appears a certain way. The earliest thing that I created that feels like the origin of my practice was a drawing that I made when I was 16. I got a piece of paper and I drew two lines across it to divide it into three equal sections. In the top third, I wrote ‘sky’, in the middle third I wrote ‘sea’, and then the bottom I wrote ‘sand’. It required the viewer to project their imagination of a landscape they've already seen, either as a painting or in the real world, to complete the work. I feel as though it was so profound that I started to use that in my own mind.

Most complex problems you encounter, either design problem or a problem in the world, if you think with lateral logic, you can come up with an answer that can flip the problem upside down, or make you see that actually there's not really a problem. That's what I'm trying to make with my work; little solutions that the world can accept and by having them, hopefully the problems just recede.

Daniel gallery

Big Brother 7 logo (Daniel Eatock, 2006)

Sky Sea Sand (Daniel Eatock, 1991)

A0 Rolling Pin painting on wood (Daniel Eatock, 2022)

MOBO billboard (Daniel Eatock, 2001)

What particular aspects of your learning at Ravensbourne did you feel were most valuable in preparing you for the MA and everything that came afterwards?

I think clarity of thoughts and removing superfluous elements and conceptual aesthetic. Figure out what it is that you're doing and then do it accurately, on time, without any fuss. It's like a modernist ethos. And that still underpins everything I do today. That's kind of the principles that I got from Ravensbourne. I had three exceptional teachers. Geoff White was amazing, very kind, gentle, knowledgeable. Rupert Bassett was clear thinking, logical and provocative. And another called Collin Maughan, who died a few years ago, who was also extremely sharp and unapologetically critical. By instilling into us this care of presentation, it made you treat them with respect. It was the first year [at Ravensbourne] that was the real basic foundations of graphic design that I'll never forget.

Talk about your involvement with Ravensbourne now and the series you’re running with our students.

My goal is to make a beautiful, complex reframe of what an exhibition is. It's all my work, but made by the students. I think it will be a really good thing for the students to be involved in.

Daniel quote

It's like mini work experience and the projects that they'll be doing are a big mixture of things. They're all linked to design in some way, because my practice stems from design, but they're not projects which they would normally encounter in a design course, so I feel as though they'll be getting quite a lot from it. ”

I don’t want to do a half-involved version of me because my whole practice is driven on honesty, truth and trying to get to the essence of something. That can be uncomfortable and difficult, but I'm prepared to go through that discomfort because ultimately the work is better at the end of it. Rather than me being a teacher, I'll be more like a curator or an art director. I can present my practice to the students and then ask if they would like to volunteer and participate.

If there was anything specific you would want a student to get from the project, what do you think that would be?

I think being proactive. The first question I asked of them is to volunteer. If they’ve volunteered and put their name on the sheet, that's the biggest hurdle right there. I think the workshops sessions that we’ll be having will be really fun because for a lot of the invitations of the work, there can't really be a bad version of it because it's they're working to quite a strict set of principles that will just lead to a good outcome. I'm hoping that it illustrates to them that if there's an idea and you follow through on that idea, the outcome is good, because the idea is good.

Are there any kind of either ongoing or upcoming projects that you are finding particularly exciting?

The paints that I use are made by Windsor Newton and they want me to make work that they can use to promote this paint. It feels really lovely because I work with their products in an unusual way, not like most painters would work with it. And for them to see that work and reach out, it feels brilliant. The collaboration with Ravensbourne, that's another thing. This is like part-curating, teaching, art directing, but there'll be an exhibition in May so that'll be a nice process to go through to get to this outcome.

I've also been invited to make some paintings for a hospital opposite Euston train station. There's a room that is used for people who have relatives who might be dying or injured where they can contemplate what’s going to happen next, so it’s quite a heavy space. That's really special because I don't make work thinking of the audience, but I want an audience for the work, because without it, there is no work. So [to make] paintings thinking that they can play a role in that environment to soothe or help someone, it just feels really a rich place to be making work for.

Are there any trends, technologies or ideas that are just coming through that you think will be prominent in the industry going forward?

Things progress at such a big rate that five years ago, AI was not in the conversation, whereas now it's the hot topic. AI could probably write a better essay than one 18-year-old could, because it's got more access to more information. But what it won't have is the feelings or the insights an 18-year-old could have if they gave their own opinion of what's going on. AI can't do that so it almost forces us to be more poetic and inward looking and understand ourselves, because that will be the point of difference. Styles change and technology evolves. You could become obsolete overnight, whereas if you understand the basic fundamentals of being human, that will be appropriate forever.